Peter Fieldman

Exactly two hundred years ago, during the winter of 1814 through to June 1815, Europe’s principal nations were locked in negotiations to determine the future of the continent at the Congress of Vienna. The participants included ambassadors from virtually every European state, region and city as well as special interest groups. Their aim was to restore or modify borders to bring peace to the continent in the aftermath of the French revolution and Napoleonic wars. So much dealing was carried out at social events, it was said that the Congress did not move but danced. One of the principal dignitaries participating at the congress was the Duke of Wellington.

However in March 1815 Napoleon escaped from the island of Elba and within 100 days had marched on Paris with his supporters to regain power. Great Britain, Russia, Prussia and Austria refused to accept his return and despite the certainty of another war with France, on 8 June 1815, the Congress ratified the treaties.

Napoleon had already mobilized his army and knew that he would have to confront a far larger Anglo-allied force under the Duke of Wellington and the Prussians led by Field Marshall Blucher, both of whose armies were camped near Brussels. Napoleon chose to strike first before the coalition forces were ready and on June 15 a minor skirmish near Charleroi resulted in the withdrawal of a Prussian force near Charleroi.

That evening, Wellington, together with many of his leading officers, were dancing at the Duchess of Richmond’s ball in Brussels when they heard about Napoleon’s surprise attack. Wellington immediately ordered a return to the field. The next forty eight hours were crucial as both sides took up their positions. A strong force led by Marechal Ney forced Wellington to withdraw northwards from Les Quatre Bras on June 16, while on June 17, Blucher’s ‘s army was defeated by the French at the battle of Lagny. He managed to withdraw during the night towards the north thus maintaining contact with Wellington who had regrouped the Anglo-Allied forces on a ridge about 1.6 kilometres south of the village of Waterloo, near Brussels. The stage was set and on the following day, Sunday June 18, one of the most decisive battles in European history took place, changing the destiny of the continent.

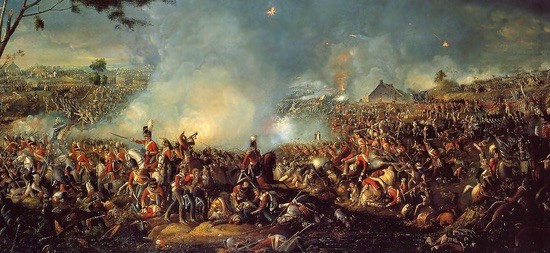

The French had mustered over seventy thousand infantry, cavalry and artillery troops. The Anglo-allied forces from Britain, the Netherlands, Brunswick and Hanover, numbered around sixty eight thousand reinforced by Blucher’s fifty thousand Prussians. The French counted on their experienced mounted lancers to charge opponents and although Wellington also used cavalry, his plan was to group his infantry in tight defensive squares. Both armies used artillery which had become a formidable weapon to weaken defences or repel attacks.

While Wellington was positioned on the north ridge, Napoleon had chosen high ground to the south, allowing both leaders to overlook the mainly flat plain, which lay between their armies from where they could implement their strategy. To the flanks were the farmhouses of Hougoumont and La Haye Sainte and a sunken road providing cover, coveted by both forces and the scene of violent combat during the day. Part of Wellington’s tactics was to use the reverse slope of the ridge to conceal his troop strength.

Nevertheless by mid afternoon the French had the upper hand having gained control of the farmhouses and were pushing back Wellington’s army. Wellington retaliated by sending in the heavy cavalry of the Scot’s Greys to charge the enemy. Coming from behind the ridge they initially surprised the French but they gradually became dispersed and were forced to pull back losing several officers in the process.

Napoleon then chose to bring in his own lancers led by Ney, but despite repeated cavalry attacks against the four man deep squares they could not break the defensive wall and were repelled under heavy fire, resulting in substantial French casualties. Unknown to Napoleon, Wellington had been in contact with Blucher for most of the day and as the French were feeling the strain of the long battle, the Prussian forces reached the battlefield and outflanked the French army, which in turn was forced to retreat in disarray. The battle was over.

Wellington was reputed to have said. “It was the nearest run thing you ever saw in your life.” Casualties were appalling. French losses exceed forty thousand while the coalition lost twenty five thousand men, either killed wounded or captured. Despite surrendering and being sent to the island of St Helena, where he remained a prisoner until his death in 1821, Napoleon is still revered and believed by many to have won the battle.

After half a lifetime of military action Wellington entered politics and ultimately became Prime Minister of England. Diplomatic agreements after the battle forged a continent of nations, which remained unchanged until the outbreak of the First World War one hundred years later. A forty-three meter high artificial hill known as the Lion Mound built in 1826, visited by thousands of people each year, stands as a memorial to the battle.