Peter Fieldman

I was born and brought up in the United Kingdom with no French connection whatsoever. Yet ever since I was a child I developed a love affair with France, especially Paris, and in 1968 in my mid-twenties I had the opportunity to work in the French capital.

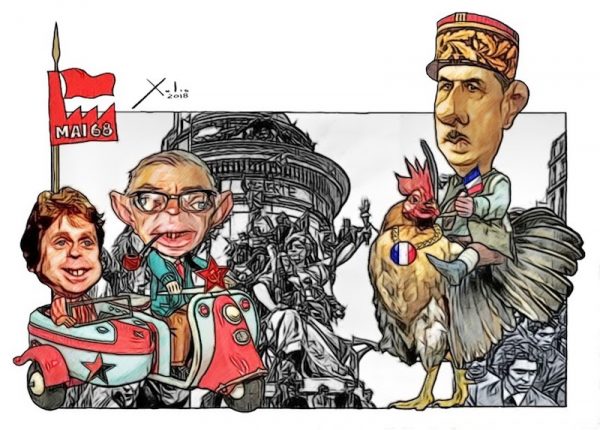

Puedes encargar un póster de este dibujo de Xulio Formoso a [email protected]

I was not to know that 1968 would turn into such an eventful year. The Tet offensive erupted in Vietnam adding to the anti-war movements gathering pace both in the USA and Europe. In April, British racing driver Jim Clark died at Hockenheim during a formula Two race and Martin Luther King was assassinated in Memphis. Then in June, Robert Kennedy, almost certainly on his way to the White House, was shot dead in California. The good news came from Wembley where Manchester United became the first English soccer club to win the European Cup.

In August I was sitting in a cafe at the Porte de Champerret engrossed in a newspaper whose headlines announced the end of the Prague Spring as Russian tanks entered the city and Alexandre Dubcek was removed from office. But two events were to affect me personally: First, Paris lived up to its romantic reputation when I met an Italian student who was to become my wife and then in May, after students and workers took to the Paris streets, I became caught up in the month long mini-revolution that shook the French state.

Thanks to general De Gaulle’s veto denying the UK’s request to join the EU, I arrived in France as a foreigner which meant queuing at the vast, daunting Prefecture building overlooking the Seine confronted by strict immigration officers and filling out a variety of forms needed to obtain a work permit. I found an apartment on the Boulevard St Martin near La Place de La Republique. Entering the building was like a scene from Les Miserables; an old wooden staircase, with the concierge’s accommodation tucked in a corner, a prostitute leaning against the wall and the odd rat which scurried into the cellar.

It did not take long to become accustomed to the vagaries of French political life under general Charles de Gaulle. With his overpowering presence it was difficult to live in Paris and be unaware of the President or his entourage. He was either loved or loathed, as the numerous attempts on his life demonstrated. The French unions, especially the CGT, were extremely powerful, which meant there was a constant threat of strikes and Paris became renowned for its street demonstrations and police presence. When De Gaulle travelled, the roads were blocked by Gendarmes using their whistles to warn everyone of the impending arrival of convoys of the legendary black Citroen DS limousines which swept out of the Elysee palace with their police motorbike escort.

During the 60s, Che Guevara, Fidel Castro and even Mao had a fascination for the young generation and in the spring when left wing students took to the streets to voice their opposition to capitalism and the consumer society there was a sense of unease. The revolt began at Nanterre University following its occupation by the students and when the Government moved in the demonstrations shifted to the Sorbonne University on the left bank.

The situation worsened when workers occupied the Renault and Citroen car plants and called for a general strike. The strikes extended to other sectors including public sector workers and taxis. Petrol became scarce due to lack of deliveries and motorists formed long queues at petrol stations while garbage piled up in the streets. Street battles with the riot police became a regular night time occurrence.

On 14 May student groups occupied the Odeon Theatre. After clambering over piles of paving stones used as barricades to enter the theatre I listened to a student, Dany “Le Rouge”, arguing for change. The debates were heated with shouting and gesturing from the audience and I felt as if I had gone back in time listening to Danton or Robespierre during the French revolution.

Boulevard Bineau was typical of the streets in Neuilly, a tree lined avenue lined with luxury apartment blocks and mansions, one of which had been converted into offices, where I worked. It was a far cry from the left bank where the paving stones (subsequently to become tourist souvenirs) were ripped up and used as weapons, and cars and barricades set on fire. Street battles with the riot police became a regular night time occurrence. My mother calling from London urged me to leave the city. “Is Paris burning?” she would ask not realising that the dramatic scenes shown on television were limited to a few streets in the Latin Quarter while the rest of Paris was unaffected. Trying to reassure her that all was well was difficult.

I was at my desk one morning when I heard the gates open and peering out of the window saw a truck reversing into the drive loaded with a huge round tank. The company director had somehow located a source of petrol outside Paris to enable the personnel to fill their cars in complete privacy and be mobile. It came just in time for the Ascension public holiday which fell on a Thursday so with Friday off work I drove down to the Loire valley with my girlfriend, Lucia, visiting the chateaux and staying in a pretty hotel by the river Cher where we had excellent meals under the shade of willow trees on the terrace, a world away from the tumult in Paris.

Despite attempts to resolve the conflict neither the Government nor the unions seemed prepared to give way and in a massive show of force the unions massed over half a million people in the streets of Paris. Then news filtered through that De Gaulle had disappeared. It transpired he had left the country and was at Baden Baden in Germany meeting an army general and rumoured to be preparing for a military repost.

A few days later, early one morning, I awoke to hear a rumbling sound shaking the building as it grew louder. I glanced out to see a convoy of tanks slowly heading along the Boulevard St Martin towards the Opera district. This is serious, I thought. From the window I saw the side street blocked by a line of CRS riot police, blocking access to the nearby Academy des Arts et Metiers whose students had also joined the demonstrations.

De Gaulle then reappeared in Paris to announce new elections and on 30 May more than three quarters of a million Gaullist supporters marched from the Place de la Concorde to the Place de l’Etoile in an emotional appeal for calm and to show that perhaps the majority of French had had enough of chaos. I stood on a bollard under the Arc de Triomphe to see the huge crowd thronging Les Champs Elysees singing the Marseillaise. The elections organised at the end of June turned out to be an overwhelming success for the Gaullist party which was returned with a massive majority; the revolt was over.

A year later, still facing criticism, De Gaulle called a referendum giving the people the opportunity to determine his future and that of the country. They voted Non and the seventy-eight, year old General gave an emotional resignation speech on television and departed to his home at Colombey Les Deux Eglises with his wife Yvonne. His decision was hardly that of a Dictator, an image conjured up by opponents. It was the end of an era during which it is said that he propelled France from the 19th to the 21st century. But he must have accepted that he was out of touch and France needed new ideas and a younger team at the helm. I cannot think of any other political leader who has followed his example.

Several years after De Gaulle’s death in 1970, driving through France to Italy with my wife, Lucia, and our two sons, I made a detour to visit the village and the simple quiet, church cemetery where he lies beside his wife in a simple grave. His refusal to be buried in the Pantheon or have a monument erected in his memory is a testament to the humility and greatness of the man although a huge forty-three, meter high cross of Lorraine, the symbol of the free French forces he led during the Second World War, dominates the surrounding hills. Before leaving, I picked up a pebble and placed it on the gravestone.

Looking back to the events of May 1968 it is interesting to consider the consequences of the revolt. It led to the demise of many of the country’s state monopolies and paved the way for the private sector, improved conditions for workers and more democracy, and accountability in the country’s institutions while liberating French youth and granting more equality for women.

For me, 1968 also brought an end to the unique charm of the Parisian lifestyle associated with Hemingway and Scott Fitzgerald. I had already visited the city several times as a teenager and had spent a summer working in a factory in the Dordogne region to improve my school French and learn to appreciate French cuisine and wine. I knew Paris when the cafes had juke boxes with huge videos projecting recordings of Johnny Halliday and other pop stars, the metro had first class carriages, the buses, open rear platforms and there were “pissoirs” in the street.The new President, Georges Pompidou had a reputation as a “bon viveur” and his period in office ushered in the celebrity age. The majority of the revolutionary students who believed in communist ideals took advantage of the post-war three decades of economic growth known as “Les Trente Glorieuses” which brought prosperity to France as well as to the rest of Western Europe. Most found well paid jobs, married, started families, purchased their homes and joined mainstream society. Dany “Le Rouge” considered one of the instigators of the student movement, used his debating talent to enter politics and under his real name, Daniel Cohn Bendit, has been for years a prominent Euro MP.

Now I find myself faced with Brexit. Although Britain has always been a reluctant member of the EU (as De Gaulle warned) and never accepted the single currency, to leave the single market is from both an economic and political viewpoint, simply inexplicable and, in my view, a major error. I sincerely hope my life will not revert to what it was when I first came to France. As a proud, albeit foreign, “Soixante Huitard” (class of 68), I could perhaps seek French nationality, but unlike my sons, I never studied philosophy, which might well rule me out.